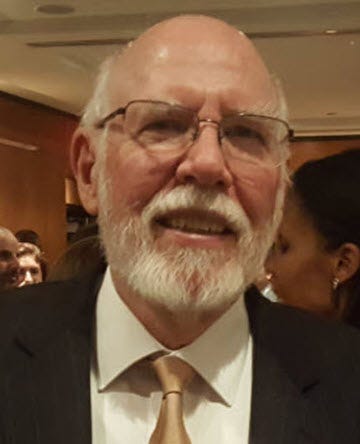

Jon Oberg is the world’s expert on corruption in the student loan program

Today, he is Mobology’s first guest columnist: "On Eliminating the U.S. Department of Education"

Dr. Jon H. Oberg has lived and worked in three capital cities. A Nebraska resident, he divides his time among Washington, D.C. (in the Maryland suburbs), Lincoln (on a prairie), and Berlin (Kreuzberg). His popular blog, Three Capitals, exhibits his extraordinary and unique perspectives, especially on U.S. politics and about those is…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to MOBOLOGY to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.